![[Column] Japanese Ambient / Environmental Music](/../assets/images/column-japanese-ambient-environmental-music.webp)

Introduction: Until silence covers the world

Text: mmr|Theme: The core of Japanese environmental music from the 1980s and its historical reappraisal

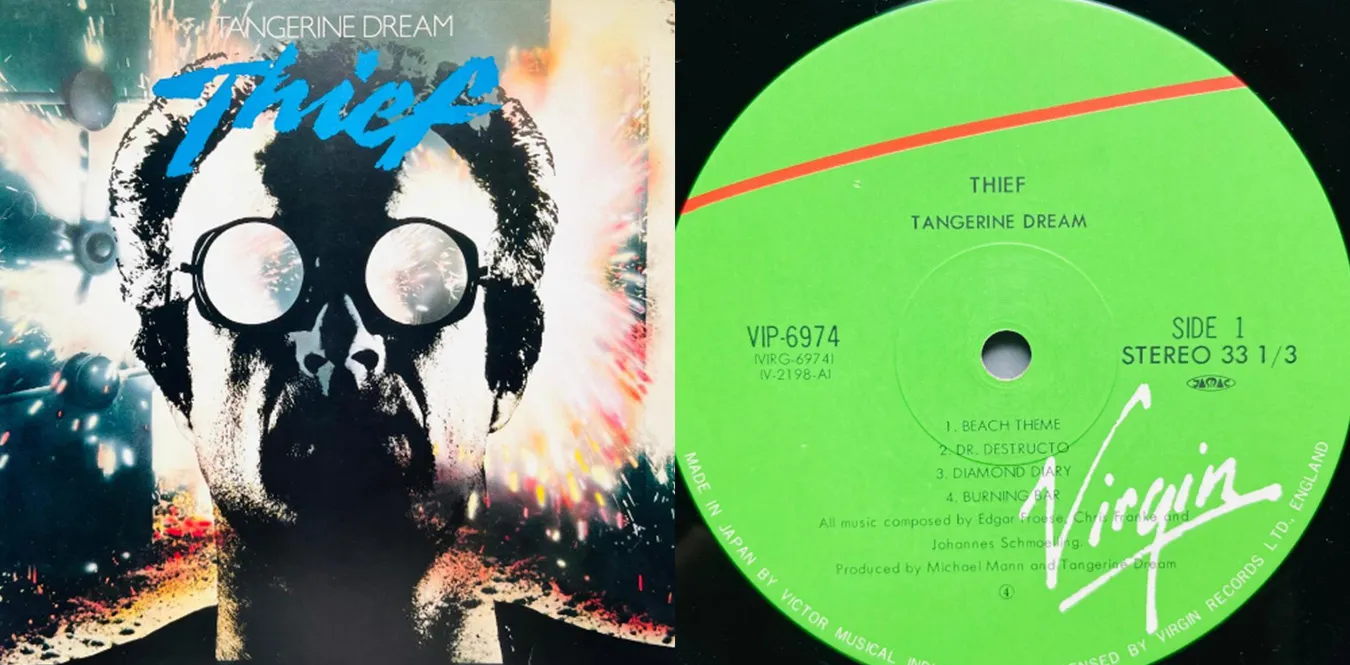

In the late 2010s, “Japanese Ambient” and “Japanese Environmental Music” began to attract a lot of attention among music listeners around the world. There are multiple reasons. These are reissues by Western labels, YouTube”s automatic recommendations, Spotify”s algorithm, and a reappraisal of electronic music/new age. However, there are important points that cannot be explained by these factors alone.

This is the fact that Japan’s ““environmental music’’ in the 1980s was born from a different cultural soil than ambient music around the world. While Western ambient music (beginning with Brian Eno) aimed at “sounds that melt into the background without stealing attention,” Japanese environmental music was closely connected to ““urban planning, architecture, commercial spaces, product design, art, consumer electronics culture, and philosophy of life.’’

The following composers were at the center of this.

- Hiroshi Yoshimura

- Midori Takada

- Takashi Kokubo

- Inoyamaland

Chapter 1: Formation of the concept of “environmental music” in Japan

● 1-1. 1970s: Experimental ground for electronic music and contemporary music

The emergence of Japanese ambient music paralleled the development of electronic music studios in the 1970s. Many universities and research institutes were researching electronic acoustics, tape music, and musique concrète, and at the same time, ““sound installations’’ increased in the field of contemporary art.

While studying spatial art at an art university, Hiroshi Yoshimura began creating works that linked the environment and sound from an early stage, and was also involved in acoustic planning for public spaces.

Japanese ambient music is characterized by being formed at the intersection of these arts, sound engineering, and urban planning.

● 1-2. “Environmental Music Series” by MUJI

In the early 1980s, MUJI aimed at ““music for consumers” and planned a series of ““environmental music” for store spaces. Hiroshi Yoshimura, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and others participated in this series, which triggered a major change in the role of sound in commercial spaces.

The feature was that it not only functioned as store background music, but was also designed to be of high quality.

● 1-3. Urbanization and the aesthetics of “tranquility”

In the 1980s, Japan experienced rapid economic growth and urbanization, but in the fields of architecture and design, ““quietness,” ““white space,” and ““simplicity’’ were talked about as virtues.

- white wall

- Minimal design using wood

- “Beauty of simplicity” symbolized by MUJI

- Zen space design

These environmental philosophies were linked to music and formed the basis for Japan’s unique “environmental music.”

Chapter 2: Trajectories of major artists

From here, we will systematically organize each artist’s career, representative works, musical characteristics, and production philosophy.

2-1. Hiroshi Yoshimura - Composer who created the foundation of Japanese environmental music

Hiroshi Yoshimura (1940–2003) is the most important composer when talking about Japanese environmental music.

● Representative works

- 《Music For Nine Post Cards》(1982) It was created with the exhibition space of an art museum in mind. Transparent piano/synth phrase.

- 《Green》(1986) One of the most highly rated works. A fusion of natural sounds and soft electronic sounds.

- 《Soundscape》 series (1986~) “Music as landscape” using field recordings.

● Musical features

- Low-key and non-repetitive

- The “space” between sounds is established as an aesthetic

- Emphasis on natural sounds and spatial resonance

● Production philosophy

Yoshimura describes music as ““light that illuminates space’‘**, We pursued “sound that changes the nature of the space, not just for appreciation.”

2-2. Midori Takada - Music of time and space drawn by percussion instruments

Midori Takada (1951–) has gained worldwide acclaim as a Japanese percussionist and composer.

● Representative works

- 《Through the Looking Glass》(1983) A masterpiece that uses percussion instruments, marimba, voice, and ethnic instruments.

- 《Lunar Cruise》(1989 / co-written with Ryo Kamomiya)

● Musical features

- Minimal structure

- Spatial handling of percussion instrument reverberations

- Applying the structure of gamelan African music

● Production philosophy

She treats percussion instruments not as symbols of “time” but as ““devices that make space sound”**, creating music that depicts a spiritual ““journey” through acoustic reverberations and overtones.

2-3. Takashi Kokubo - Explorer of comfort and living acoustics

Takashi Kokubo (1956-), after a career in sound effects production and broadcast audio, has released numerous works with the theme of “comfortable acoustics” since the 1980s.

● Representative works

- 《Ion Series》(1980s~) An environmental music series produced as a CD that comes with air purifiers.

- 《A Dream Sails Out To Sea》(1987) After recurrence, the patient was reevaluated overseas.

● Musical features

- Fusion of natural and electronic sounds

- Empirical approach to relaxation acoustics

- “Functional ambient” created by collaboration with household appliances

2-4. Inoyama Land - Pastoralism and landscape description of electronic sounds

The duo ““Inoyamaland’’ consisting of Yasushi Yamashita and Makoto Inoue has a unique style that straddles the line between techno pop and environmental music.

● Representative works

- 《Danzindan-Pojidon》(1983) An electronic yet idyllic masterpiece.

- 《INOYAMA LAND》(1997)

● Musical features

- Soft electronic sounds

- Sound themed around “children”s worldview”

- Emphasis on the gentle texture of the synthesizer

Chapter 3: The technological foundation that supported Japanese environmental music

● 3-1. Synthesizer culture

In the 1980s, Japanese electronic musical instrument manufacturers dominated the world market and had a great influence on ambient music.

Equipment that was often used (within the range that can be confirmed as fact)

- Yamaha DX7

- Roland Juno series

- Roland RE-201 (tape echo)

- Korg analog model

- Field recorder (cassette/reel-to-reel)

● 3-2. Home recording and home studio culture

Home recording equipment became widespread in Japan early on, and many composers conducted experimental sound production at home. This was a major feature compared to Europe and America, and became the background for the deepening of environmental music on an individual level.

● 3-3. Cooperation with acoustic design and architecture

Hiroshi Yoshimura and Inoyama Land also participated in the acoustic design of architectural spaces, public facilities, corporate showrooms, etc., and emphasis was placed on the functionality of music and its influence on space.

Chapter 4: Connection between commercial space/urban culture and environmental music

● 4-1. MUJI, PARCO, department store BGM

Commercial facilities in Tokyo in the 1980s focused on music design, “Acoustics that improve the quality of life” was raised as a theme.

In this context, environmental music went beyond mere background music and became an element that shaped the impression of the space.

● 4-2. Connection with “comfort functions” of home appliances

Takashi Kokubo’s music that comes with air purifiers is a symbol of this. Home appliances x environmental acoustics He established a uniquely Japanese idea.

This is an extremely unique cultural phenomenon worldwide.

Chapter 5: Modern Reassessment and Implications

● 5-1. Relapse rush in the 2010s

A series of reissues by European and American labels,

- Hiroshi Yoshimura

- Midori Takada

- Takashi Kokubo

- Inoyama Land His works are now available in record shops around the world.

● 5-2. Dissemination on video sites

Due to YouTube’s algorithm, the number of views for “Green” and “Through the Looking Glass” has increased significantly. This created a global listener base.

● 5-3. Influence on modern ambient music

Many of the ambient composers of the 2020s cite Japan’s 1980s environmental music as an influence.

The reason is Unique acoustic aesthetics that harmonizes melody and silence This is because it is extremely modern.

Chapter 6: 1970–2020s Timeline

| Year | Events |

|---|---|

| 1970s | Development of electronic music and sound art |

| 1975 | Hiroshi Yoshimura is involved in environmental music planning |

| 1980 | MUJI begins preparations for environmental music series |

| 1982 | Hiroshi Yoshimura《Music For Nine Post Cards》 |

| 1983 | Midori Takada《Through the Looking Glass》, Inoyama Land《Danzindan-Pojidon》 |

| 1986 | Hiroshi Yoshimura《Green》 |

| 1987 | Takashi Kokubo《A Dream Sails Out To Sea》 |

| 1990s | Distribution of some works stopped / On the eve of re-evaluation |

| 2010s | Recurrence in Europe and America, global reevaluation |

| 2020s | Exhibitions and reprints continue and it becomes an international genre |

Chapter 7: Relationship diagram between major artists and context

Environmental music project] --> YH[Hiroshi Yoshimura] YH --> JP[Establishment of 80s environmental music] MT[Midori Takada] --> JP TK[Takashi Kokubo] --> JP INO[Inoyama Land] --> JP JP --> RE[2010s re-evaluation] RE --> WW[global ambient boom]

Chapter 8: Summary - Why Japanese environmental music captivates the world

Japanese environmental music is not just “healing” or “background sound.” Sound art created by urban culture, design, and philosophy of life It is.

- Intermediate area between art and music

- Response to urbanization

- Lifestyle culture and home appliance technology

- Synthesizer innovation

- Collaboration with spatial design

All of these were present in Japan in the 1980s.

The world has reevaluated the Not only the beauty of the music itself, but also the unique Japanese philosophy contained within it It is.

Ambient music continues to have new meanings around the world, and the works from the 1980s that gave rise to it are likely to remain an important foundation of music history.

![[Column] Penguin Cafe Orchestra - An imaginary paradise that resonates between ambient and folklore](/../assets/images/column-penguin-cafe-orchestra.webp)

![[Column] Ambient: From](/../assets/images/column-ambient2.webp)

![[Column] What is ambient music? Philosophy of](/../assets/images/column-ambient.webp)